The archaeology of Israel is the study of the archaeology of the present-day Israel, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented…

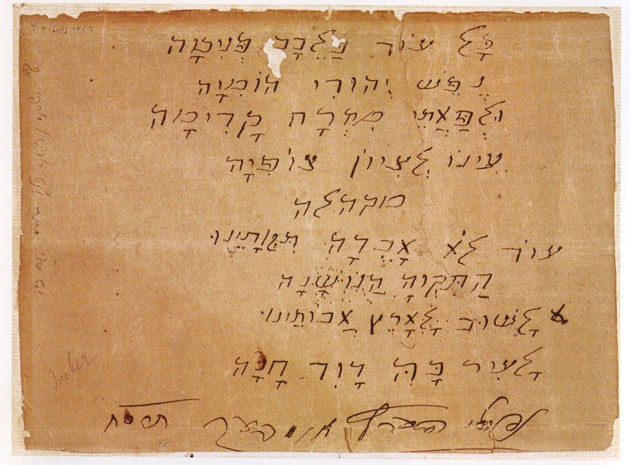

#82 Hatikvah

Hatikvah is Israel’s national anthem and the song that brings tears to eyes of Jews around the world. Part of 19th-century Jewish poetry, the theme of the Romantic composition reflects the 2,000-year-old desire of the Jewish people to return to the Land of Israel and reclaim it as a free and sovereign nation. The piece’s lyrics are adapted from a work by Naftali Herz Imber, a Jewish poet from Złoczów, Austrian Galicia. Imber wrote the first version of the poem in 1877, while he was hosted by a Jewish scholar in Iași, Romania.

History

The text of Hatikvah was written in 1878 by Naftali Herz Imber, a Jewish poet from Zolochiv (Polish: Złoczów), a city nicknamed “The City of Poets”, then in Austrian Poland, today in Ukraine. His words “Lashuv le’eretz avotenu” (to return to the land of our forefathers) expressed its aspiration.

In 1882, Imber emigrated to Ottoman-ruled Palestine and read his poem to the pioneers of the early Jewish villages—Rishon LeZion, Rehovot, Gedera, and Yesud Hama’ala.[3] In 1887, Samuel or Shmuel Cohen, a very young (17 or 18 years old) resident of Rishon LeZion with a musical background, sang the poem by using a melody he knew from Romania and making it into a song, after witnessing the emotional responses of the Jewish farmers who had heard the poem. Cohen’s musical adaptation served as a catalyst and facilitated the poem’s rapid spread throughout the Zionist communities of Palestine.

Imber’s nine-stanza poem, “Tikvatenu” (“Our Hope”), put into words his thoughts and feelings following the establishment of Petah Tikva (literally “Opening of Hope”). Published in Imber’s first book Barkai [The Shining Morning Star], Jerusalem, 1886, was subsequently adopted as an anthem by the Hovevei Zion and later by the Zionist Movement.

Before the founding of Israel

The Zionist Organization conducted two competitions for an anthem, the first in 1898 and the second, at the Fourth Zionist Congress, in 1900. The quality of the entries were all judged unsatisfactory and none was selected. Imber’s “Tikvatenu”, however, was popular, and a sessions at the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1901 concluded with the singing of the poem. During the Sixth Zionist Congress at Basel in 1903, the poem was sung by those opposed to accepting the proposal for a Jewish state in Uganda, their position in favor of the Jewish homeland in Palestine expressed in the line “An eye still gazes toward Zion”.

Although the poem was sung at subsequent congresses, it was only at the Eighteenth Zionist Congress in Prague in 1933 that a motion passed formally adopting “Hatikvah” as the anthem of the Zionist movement.

The British Mandate government briefly banned its public performance and broadcast from 1919, in response to an increase in Arab anti-Zionist political activity.

A former member of the Sonderkommando reported that the song was spontaneously sung by Czech Jews at the entrance to the Auschwitz-Birkenau gas chamber in 1944. While singing they were beaten by Waffen-SS guards.

Adoption as the Israeli national anthem

When the State of Israel was established in 1948, “Hatikvah” was unofficially proclaimed the national anthem. It did not officially become the national anthem until November 2004, when an abbreviated and edited version was sanctioned by the Knesset in an amendment to the Flag and Coat-of-Arms Law (now renamed the Flag, Coat-of-Arms, and National Anthem Law).

In its modern rendering, the official text of the anthem incorporates only the first stanza and refrain of the original poem. The predominant theme in the remaining stanzas is the establishment of a sovereign and free nation in the Land of Israel, a hope largely seen as fulfilled with the founding of the State of Israel.

Musical composition

The melody for “Hatikvah” derives from “La Mantovana”, a 16th-century Italian song, composed by Giuseppe Cenci (Giuseppino del Biado) ca. 1600 with the text “Fuggi, fuggi, fuggi da questo cielo”. Its earliest known appearance in print was in the del Biado’s collection of madrigals. It was later known in early 17th-century Italy as Ballo di Mantova. This melody gained wide currency in Renaissance Europe, under various titles, such as the Pod Krakowem (in Polish), Cucuruz cu frunza-n sus [Maize with up-standing leaves] (in Romanian) and the Kateryna Kucheryava (in Ukrainian). It also served as a basis for a number of folk songs throughout Central Europe, for example the popular Slovenian children song Čuk se je oženil [The little owl got married] (in Slovenian). The melody was used by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana in his set of six symphonic poems celebrating Bohemia, Má vlast (My Homeland), namely in the second poem named after the river which flows through Prague, Vltava. The melody was also used by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns in Rhapsodie bretonne.

The adaptation of the music for “Hatikvah” was set by Samuel Cohen in 1888. Cohen himself recalled many years later that he had hummed “Hatikvah” based on the melody from the song he had heard in Romania, “Carul cu boi” (the ox-driven cart).

The harmony of “Hatikvah” follows a minor scale, which is often perceived as mournful in tone and is uncommon in national anthems. As the title “The Hope” and the words suggest, the import of the song is optimistic and the overall spirit uplifting.

Usage in film

American composer John Williams adapted “Hatikvah” in the 2005 historical drama film Munich.

“Hatikvah” is also used both in the adaptation of Leon Uris’s novel, Exodus, and in the 1993 film Schindler’s List.[citation needed]

In 2022 Roman Shumunov filmed a TV series titled As Long as in the Heart [he] about the Israeli youth encounter with The Holocaust.

Renditions, interpretations, and usage in popular music

Barbra Streisand performed “Hatikvah” in 1978 at a televised music special called The Stars Salute Israel at 30, a performance which included a conversation by telephone and video link with former Prime Minister Golda Meir.

American musician Anderson .Paak’s 2016 release “Come Down” contains a sample of “Hatikvah” in English translation, attributed to producer Hi-Tek.

A 2018 rendition of the anthem by Israeli Jewish singer Daniel Sa’adon that took inspiration from the Levantine music and dance style dabke caused controversy and accusations of appropriation of Palestinian culture, as well as consternation from some Israelis due to the tune’s popularity with Hamas. Sa’adon, however, said that his desire was to “show that the unity of cultures is possible through music”,[21] and that he has a longtime appreciation for Southwest Asian and North African musical styles, having grown up with Tunisian music in the home. Sa’adon said that despite receiving “abusive comments” from both the right and the left of the political spectrum, he also received praise from friends and colleagues in the music world, including Palestinian Israelis.

Official text

The official text of the Israeli national anthem corresponds to the first stanza and amended refrain of the original nine-stanza poem by Naftali Herz Imber. Along with the original Hebrew, the corresponding transliteration and English translation are listed below.

English translation

As long as in the heart, within,

The soul of a Jew still yearns,

And onward, towards the ends of the east,

an eye still gazes toward Zion;

Our hope is not yet lost,

The hope of two thousand years,

To be a free nation in our land,

The land of Zion and Jerusalem.